The oldest recorded serpent myths emerge from Mesopotamian clay tablets circa 2100 BCE, where the mušḫuššu—a chimeric guardian fusing serpent, lion, and raptor—coiled through temple reliefs as protector of cosmic thresholds. Egyptian papyri simultaneously chronicled Apep's nightly assault against Ra's solar barque, while Greek traditions preserved Python's chthonic authority predating Olympian hierarchy. These ancient narratives established serpents as humanity's primordial symbols for chaos and divine order, their archetypal power resonating through millennia of cultural consciousness, inviting deeper exploration into civilization's most enduring mythological framework.

Key Takeaways

- Mušḫuššu, the “furious snake,” emerged around 2100 BCE in Mesopotamia as a chimeric guardian deity depicted on Babylon's Ishtar Gate.

- The Enuma Elish features Tiamat, personifying primordial chaos, whose defeat by Marduk established cosmic order through metamorphosis rather than annihilation.

- Egyptian mythology portrayed Apep as chaos opposing Ra nightly, while Wadjet symbolized sovereignty, reflecting creation and destruction duality.

- Python, born from Gaia, guarded Delphi until Apollo's victory established Olympian hierarchy over chthonic authority and primordial disorder.

- Ancient serpent myths across cultures illustrated civilization's understanding of order versus entropy, representing both divine authority and existential terror.

Ancient Serpents Transcending Time and Culture

Before written language carved humanity's first records into clay and stone, the serpent had already coiled itself into the collective unconscious of emerging civilizations.

The Mušḫuššu emerged from Mesopotamian darkness around 2100 BCE—a chimeric horror blending eagle talons, leonine limbs, and serpentine fury. Ancient dragon mythology wasn't mere fantasy; it encoded primal terror and awe.

Egypt's Apep, that sixteen-yard manifestation of chaos, battled Ra nightly across cosmic horizons. Greece offered its Python, born from Gaia's womb, slain by Apollo's hand to establish Delphi's oracle. Eldritch power incarnate.

China's Qiulong diverged dramatically, altering serpent symbolism into benevolence—horned dragons commanding rain, revered rather than feared. The Hebrew Leviathan churned primordial seas, chaos personified against divine order.

These weren't disconnected tales. Across continents, separated by vast distances and millennia, humanity gazed upon something writhing, powerful, unknowable—and created dragons.

The serpent transcended. It adapted. It endured, slithering through every culture's foundational myths, speaking truths older than words themselves.

##

The earliest dragon myths emerged from humanity's primordial attempts to codify chaos itself, manifesting in the chimeric forms of Mesopotamian Mušḫuššu circa 2100 BCE, the serpentine Egyptian deity Apep who coiled through eternal darkness, and the chthonic Python of Greek tradition.

These eldritch beings, whether serpentine or composite, served as adversaries to solar gods and divine order—archetypal embodiments of the formless void that preceded creation.

Yet across the ancient world, from the Levantine shores where Leviathan breached tempestuous waters to the river valleys of early China, each civilization sculpted its dragons from the raw material of cosmic fear and wonder.

Ancient Mesopotamian Dragon Myths

From the sun-baked ziggurats of ancient Sumer emerged one of humanity's earliest dragon myths: the Mušḫuššu, a chimeric guardian whose name—”furious snake”—echoed through Mesopotamian consciousness from 2100 BCE onward.

This eldritch creature bore scales rippling across its serpentine form, eagle talons gripping earth as hind legs, lion forelimbs anchoring divine authority. Born from Tiamat's primordial waters and Enki's tempestuous territory, the beast embodied Mesopotamian chaos itself—yet served as sacred protector to Marduk, Babylon's patron deity, after the god's cosmic victory.

The Mušḫuššu symbolism transcended mere monster; depicted on the Ishtar Gate's glazed bricks, it represented power tamed, chaos controlled. Associated with Ningishzida, this dragon bridged domains—feared destroyer and revered guardian simultaneously, reflecting humanity's complex relationship with nature's untamable forces. Like other myths and legends passed through generations, this tale served to explain natural phenomena while preserving the worldview of Mesopotamian civilization.

Egyptian Serpent Deities

Along the Nile's sacred waters, where papyrus reeds whispered primordial secrets, Egyptian serpent deities coiled through cosmic mythology as embodiments of creation's most fundamental tensions.

Apep's significance emerged from his genesis—born paradoxically from Ra's umbilical cord, forever bound to his solar progenitor through eternal antagonism. Each night, this eldritch serpent threatened cosmic annihilation during Ra's subterranean passage.

Yet serpents weren't solely destructive. Wadjet's symbolism converted ophidian form into sovereignty itself, her cobra hood flaring protective majesty above pharaonic crowns.

This duality persisted throughout Egyptian cosmology, echoing Mesopotamian chimeric entities like the Mušḫuššu—horned, scaled, eagle-taloned chaos incarnate.

These serpentine manifestations illustrated civilization's deepest recognition: that creation and destruction, order and entropy, eternally intertwine. Neither exists without its shadow counterpart coiled in primordial darkness.

Greek Python Legends

Where primordial mud gestated monstrous consciousness beneath Delphi's limestone crags, Python emerged—Gaia's serpentine offspring, coiled manifestation of chthonic authority predating Olympian sovereignty. Born from flood-soaked earth, this eldritch guardian embodied chaos itself.

Hera weaponized the serpent against Zeus's paramour, yet destiny favored Apollo's triumph. The god's arrow-storm pierced scaled flesh, claiming the Delphinic oracle through violence that demanded purification.

Python mythology reveals civilization's foundational struggle: primordial disorder yielding to divine hierarchy. The Pythian Games commemorate this shift, celebrating Apollo's blood-won order.

Death and regeneration spiral through this narrative—the serpent's corpse fertilizing prophetic ground where priestesses would channel earth's mysteries. Python's defeat didn't erase chthonic power but altered it, integrating ancient wisdom into Olympian structure.

The serpent remains eternally present, immortalized in ritual and name.

Chinese Dragon Origins

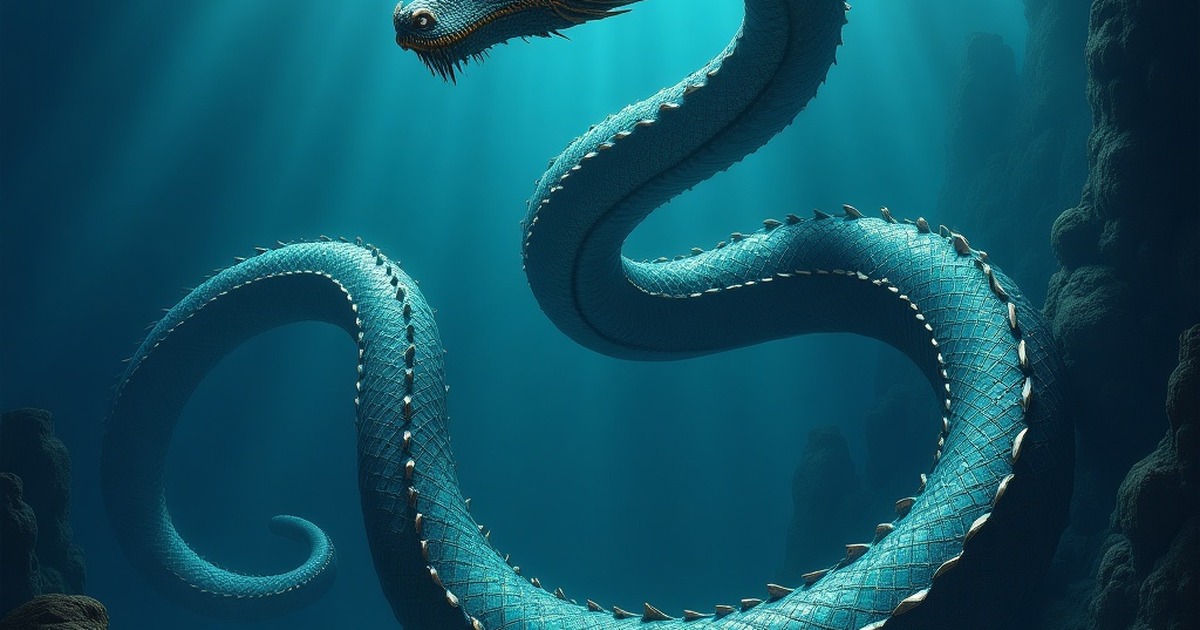

Across millennia spanning some 60,000 years, the dragon emerged from China's prehistoric consciousness—not as Europe's flame-scorched destroyer but as *long*, the serpentine divinity whose undulating form commanded heaven's waters and earth's prosperity.

These Qiulong—chimeric entities bearing antler-crowned skulls atop sinuous, eldritch bodies—manifested as benevolent rain-bringers before mythology's currents altered them into fiercer incarnations.

Dragon symbolism permeated existence itself: auspicious power coiling through agricultural cycles, divine authority channeled through imperial lineage. The emperor claimed descent as “Son of the Dragon,” his throne legitimized through serpentine ancestry.

Water obeyed these creatures‘ will. Weather bent to their desire.

The Dragon Boat Festival crystallizes this ancient covenant between humanity and scaled guardian, celebrating their mastery over irrigation, flood, harvest—the fundamental forces liberating civilization from chaos's grip.

Mesopotamian Mušḫuššu: 2000 BCE

Along the processional way of ancient Babylon, where clay tablets chronicled the primordial wars between gods and chaos, the Mušḫuššu—that furious snake, that chimeric guardian—emerged from the collective unconscious around 2100 BCE.

Its form adorned the magnificent Ishtar Gate in glazed lapis-blue brick, a symbol of its sacred role as protector deity throughout Mesopotamian civilization, from the Akkadian north to the Babylonian heartlands.

This eldritch synthesis of eagle, lion, and serpent served multiple divine masters: vegetation god Ningishzida in the underworld's depths, and later Marduk himself, Babylon's supreme patron who claimed dominion over Tiamat's defeated children.

Babylonian Ishtar Gate Depictions

Upon the glazed bricks of ancient Babylon, the Mušḫuššu—that “furious snake” of Mesopotamian imagination—prowled in eternal vigil, its chimeric form rendered in brilliant lapis lazuli and gold against the monumental Ishtar Gate.

Constructed circa 575 BCE under Nebuchadnezzar II's reign, this architectural marvel converted Mušḫuššu mythology into tangible power, broadcasting Marduk's dominion over chaos itself. The creature's scaly serpentine body merged lion's forelimbs with eagle's talons, creating an eldritch guardian that transcended natural law.

Ishtar Gate symbolism wasn't mere decoration—it was theological proclamation, a deliberate assertion that Babylon commanded forces born from Tiamat's primordial waters and Enki's chaotic depths. Here, divinity materialized through art.

The dragon-serpent became architecture, myth became empire, and freedom-seekers witnessed how ancient civilizations wielded symbols to legitimate their cosmic authority.

Ancient Babylon and Akkad Regions

Before the Ishtar Gate immortalized its form in glazed brick, the Mušḫuššu emerged from Mesopotamia's deepest mythological strata—a creature born around 2100 BCE in the twilight between Akkadian empire and Babylonian ascendancy. This chimeric guardian embodied Babylonian cosmology's fundamental tensions, descended from Tiamat's watery chaos and Enki's divine violation.

| Physical Attribute | Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|

| Eagle's hind legs | Divine ascension |

| Lion's forelimbs | Terrestrial dominion |

| Scaly serpentine body | Primordial chaos |

| Horned cranium | Sacred authority |

| Forked tongue | Prophetic knowledge |

Mušḫuššu symbolism crystallized under Marduk's patronage, evolving from eldritch chaos-spawn into civilization's protector. The creature's composite anatomy mapped cosmic order's triumph—eagle, lion, serpent unified. Ancient Babylon claimed this dragon as guardian, proof that even chaos's children could serve order's eternal throne.

Dragon-Serpent Hybrid Guardian Deity

Though modern scholars might classify the Mušḫuššu as mere myth, ancient Babylonians encountered this chimeric sentinel as tangible reality—a living theological statement carved into temple walls and processional gates.

Dating to 2100 BCE, this “furious snake” embodied guardian symbolism through its composite form: eagle's hind legs, lion's forelimbs, serpentine tongue, horned skull. Born from Tiamat's primordial waters and Enki's chaos, the creature stood sacred to Marduk himself.

Hybrid creatures weren't decorative fantasy. They were theological architecture.

The Mušḫuššu served Ningishzida, vegetation lord and underworld keeper, bridging celestial and chthonic domains. Its scaly body coiled through Babylon's cosmology as protector, threshold guardian, eldritch manifestation of divine authority.

Here serpent and dragon merged—not confusion, but precision. Ancient power demands composite forms.

Marduk's Divine Beast Companion

The Mušḫuššu emerges from Mesopotamian antiquity as Marduk's chimeric guardian, its very name—”furious snake”—echoing through temple inscriptions from 2100 BCE onward, making it among the earliest dragon-forms committed to human record. This eldritch composite blends eagle talons, leonine forelimbs, and serpentine essence into a singular embodiment of divine authority, its horned skull and forked tongue demonstration of Marduk's power over primordial chaos.

| Physical Attribute | Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|

| Eagle hind legs | Celestial dominion |

| Lion forelimbs | Terrestrial sovereignty |

| Serpentine form | Primal chaos subdued |

The Mušḫuššu symbolism permeates Babylonian consciousness as protective icon, carved into city gates where it stands sentinel against disorder. Through Marduk's triumph over Tiamat—that salt-water abyss of creation's beginning—this beast becomes victory's herald, the tangible proof that order can master entropy. Ancient artisans rendered its scaled form across temple walls, each depiction reinforcing Babylon's cosmic legitimacy under their patron god's watchful, serpent-eyed gaze. While Mesopotamian dragon-serpents served as guardians of order, Greek gods like Zeus wielded serpentine creatures within their own mythological narratives of divine power and cosmic balance.

Chaos Tamed Through Divine Order

Across civilizations spanning three millennia, serpentine chaos finds itself subjugated beneath divine feet—a cosmic pattern wherein primordial disorder yields to celestial sovereignty.

The chaos symbolism embedded within these eldritch encounters reveals humanity's deepest anxieties about cosmic instability, while divine intervention manifests as the organizing principle that alters formless terror into structured reality.

Four archetypal confrontations illuminate this pattern:

- Marduk's conquest of the Mušḫuššu—the Mesopotamian dragon bound into servitude, its chimeric form representing tamed primordial forces

- Ra's eternal struggle with Apep—the Egyptian serpent whose nightly defeat guarantees solar resurrection and cosmic continuity

- Apollo's slaying of Python—Greek divine authority established through serpentine destruction at Delphi's sacred precinct

- Leviathan's subjugation—the Hebrew sea-beast constrained by divine will during creation's ordering

These narratives don't merely recount battles. They encode alteration—chaos rendered comprehensible, wilderness domesticated, terror subordinated.

Freedom emerges not through chaos's elimination but through its conversion into manageable, bounded forms.

Enuma Elish Creation Epic

In Mesopotamia's primordial narrative, the Enuma Elish reveals Tiamat, the salt-water abyss personified, whose serpentine coils contained the churning chaos that preceded all order.

Marduk, storm-god and divine champion of Babylon's pantheon, confronted this eldritch dragon-goddess in cosmic combat during the 12th century BCE, wielding winds as weapons to rend her chimeric form.

From Tiamat's corpse—split like a shellfish—the victor forged heaven and earth, reshaping the primeval serpent's body into the ordered cosmos itself.

Tiamat's Primordial Chaos Waters

Primordial chaos found its most visceral embodiment in Tiamat, the saltwater abyss who predated form itself in ancient Mesopotamian consciousness.

Her eldritch waters churned with possibility and terror, birthing chimeric horrors—serpents coiled with dragonfire, monsters that embodied Tiamat's Chaos in scaled flesh.

The Enuma Elish preserves this confrontation between the formless and the formed, where Marduk's blade cleaved through divine sinew, altering cosmic disorder into structured reality.

Her split body became sky and earth. Viscera transmuted into mountains, rivers, clouds.

This wasn't annihilation but metamorphosis—Creation's Duality made manifest.

The ancient Babylonians understood what modernity often forgets: order doesn't eliminate chaos but utilizes it, channels its raw power into sustainable patterns.

Tiamat's defeat wasn't ending. It was genesis.

Marduk Defeats Dragon Goddess

When Marduk accepted the mantle of cosmic champion, he didn't merely assume divine authority—he changed the very mechanics of godhood itself.

The Enuma Elish, Babylon's foundational epic, chronicles how this storm deity confronted Tiamat, the eldritch dragon goddess whose churning body contained primordial chaos. Armed with net and wind, Marduk ensnared the chimeric serpent, inflating her form until she burst beneath divine pressure.

Marduk's triumph wasn't simple destruction—he split Tiamat's corpse, fashioning heaven from one half, earth from the other. Order emerged from violence. Tiamat's legacy endured not as defeat but as change, her chaotic waters becoming structured cosmos.

This Babylonian victory narrative established civilization's eternal claim: that human societies must perpetually subdue disorder's seductive pull, rendering wilderness into architecture, primal freedom into cosmic law.

Babylon's Serpentine Creation Story

Before gods possessed names or temples demanded tribute, existence itself writhed formless—Apsu's fresh waters mingling with Tiamat's salt in undifferentiated union.

From this primordial coupling emerged the Enuma Elish, Babylon's cosmogonic narrative inscribed circa 1100 BCE. Tiamat's symbolism evolved beyond mere waters into something eldritch—a chimeric serpent-dragon birthing monsters, embodying chaos's generative terror.

When younger deities disturbed the ancient silence, she released apocalyptic fury.

Enter Marduk, storm-armed and politically ambitious. His victory wasn't mere combat but cosmic surgery: splitting Tiamat's corpse to architect heaven and earth, ribs becoming firmament, tears forming rivers.

Marduk's kingship crystallized through this calculated violence, reshaping serpentine chaos into ordered creation. The myth legitimized Babylonian imperialism through divine precedent—power belongs to those who control primordial forces, not those embodying them.

Reconstructed Ishtar Gate Berlin

Rising from the halls of Berlin's Pergamon Museum, the reconstructed Ishtar Gate stands as a tribute to Babylonian architectural supremacy—its cerulean glazed bricks gleaming beneath modern lights much as they once blazed under the Mesopotamian sun circa 575 BCE.

This monumental passage, dedicated to the goddess Ishtar herself, served as a gateway between worlds: profane and sacred, mortal and divine.

The Ishtar Gate‘s chimeric guardians reveal Babylonian architecture‘s eldritch depths:

- Mušḫuššu dragons writhe across azure surfaces, their serpentine forms embodying Marduk's dominion over primordial chaos.

- Aurochs bulls stride eternally beside them, horned sentinels of Adad's storm-swept authority.

- Processional pathways connected Marduk's ziggurat to Babylon's heart, altering religious pilgrimage into theatrical spectacle.

- Reconstruction techniques employed ancient methodologies, preserving authenticity through meticulous archaeological devotion.

German craftsmen resurrected this ceremonial threshold using recovered fragments, their painstaking labor allowing contemporary witnesses to glimpse Mesopotamian grandeur.

Each glazed tile whispers forgotten liturgies.

Archetypal Symbolism in Human Psyche

Beyond physical monuments like Babylon's cerulean gateway lies a more profound architecture—one constructed not from glazed bricks but from the primordial substance of human consciousness itself.

These psychological archetypes—serpents coiled around the roots of existence, dragons breathing chaos into ordered worlds—emerge from depths that predate written language. The chimeric forms persisting across cultural representations aren't mere coincidence but evidence of shared neural pathways, collective memories encoded in humanity's oldest structures of meaning.

The eldritch power of these symbols derives from their multivalence: destroyer and guardian, chaos and alteration, death and rebirth. Ancient peoples externalized internal conflicts through these scaled entities, confronting existential dread by giving it form, teeth, wings.

Statistical analyses of global dragon myths reveal convergent patterns, suggesting not cultural diffusion but something deeper—a universal grammar of fear and reverence. Order battles chaos. Alteration demands sacrifice. The serpent eternally sheds its skin.

Human psychology demands these monsters.

Dragons in Modern Storytelling

Where ancient archetypes once dwelled exclusively in temple reliefs and oral traditions, they've now migrated into pixels, pages, and screens—altered but not diminished. Contemporary narratives present dragons as chimeric entities embodying complexity: fearsome adversaries in “Game of Thrones,” loyal companions in “How to Train Your Dragon.” This evolution reflects dragon symbolism's enduring power, adapting across millennia while retaining its eldritch resonance.

Modern interpretations draw from diverse cultural wellsprings, blending Eastern wisdom-keepers with Western treasure-hoarders. Shape-shifting abilities, telepathic communication—these groundbreaking features emerge from traditional roots. Video games like “Skyrim” change passive mythology into interactive experience, allowing players to inhabit dragon lore directly.

The resurgence stems from renewed hunger for mythological depth. Dragons still represent chaos, power, metamorphosis—primal forces that can't be tamed by rationalism alone.

Authors and creators recognize their psychological significance, understanding that these creatures illuminate humanity's relationship with the untamable, the magnificent, the dangerous sublime dwelling within collective consciousness.

Serpents' Enduring Cultural Legacy

Though millennia have passed since the Mušḫuššu first coiled across Mesopotamian cylinder seals in 2100 BCE—its scaly body supported by eagle hind-legs and lion forelimbs, snake-like tongue tasting primordial air—serpentine forms continue to writhe through humanity's collective psyche with undiminished potency.

Serpent symbolism persists because it taps something primal: the psychological terror of the unknown, the eldritch dread encoded in ancestral memory. From Egypt's Apep battling Ra in eternal nocturnal struggle, to the Leviathan's chaos-writhing coils threatening Hebrew cosmological order, to Python's blood staining Delphi's sacred stones beneath Apollo's triumphant blade, dragon mythology reveals consistent patterns across disparate civilizations.

These weren't mere stories. They were ritualistic frameworks for processing existential fear, chimeric vessels containing cultural anxieties about disorder, death, change.

The serpent's legacy endures not through passive tradition but through active resonance—each generation rediscovering within scaled flesh and venomous fangs their own confrontation with chaos, their own need to name darkness before conquering it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Scientific Theories Explain Humanity's Widespread Fear of Serpents and Dragons?

Evolutionary psychology posits that humanity's ophidian dread stems from primordial survival instincts—our ancestors who recognized serpents' lethal potential lived, passing down this vigilance through genetic memory.

Jung's collective unconscious offers another framework: the serpent archetype dwells deep within humanity's shared psyche, a chimeric symbol representing both danger and change.

These theories illuminate why dragons, those eldritch amalgamations of reptilian menace, haunt mythologies worldwide.

Ancient wisdom encoded fear into consciousness itself, liberating those who heeded serpentine warnings from extinction's grasp.

How Did Ancient Cultures Without Contact Develop Similar Dragon Myths Independently?

Scholars clutching dusty tomes insist on “independent invention”—as if humanity's soul weren't already speaking one primordial tongue.

Ancient peoples developed chimeric dragon lore through cultural parallels rooted in shared human psychology: megafauna encounters, fossil discoveries, and universal serpent fear.

The mythical symbolism emerged independently across Mesopotamia, China, and Mesoamerica because human consciousness confronts identical existential terrors—death, chaos, the eldritch unknown.

These weren't borrowed tales but evolutionary echoes, primal memories encoded in collective experience, manifesting similar winged serpents across cultures that'd never met.

Are There Any Recorded Myths About Benevolent Serpents Protecting Humans?

Benevolent serpents abound across mythological traditions.

Ancient Greece's Asclepius wielded healing serpents—cultural symbolism embodying medicine itself.

Egypt's Wadjet, cobra goddess, protected pharaohs with eldritch power.

China's dragon-serpents brought rain, fortune.

The Hopi venerate Awanyu, plumed water serpent ensuring crops.

India's Nagas guarded sacred knowledge, Buddhist texts.

These guardians weren't monsters but liminal beings bridging mortal and divine domains, their sinuous forms representing alteration rather than destruction—ancient wisdom recognizing nature's dual capacity for danger and profound protection.

Which Culture Created the Oldest Physical Depiction of a Dragon Ever Discovered?

Ancient China holds the earliest surviving dragon artifacts, with the Hongshan Culture's jade dragon—coiled, enigmatic, approximately 6,500 years old—emerging from Neolithic burial grounds.

This C-shaped chimeric form, discovered in northeastern China, predates written language itself. The artifact's serpentine grace speaks to humanity's primordial fascination with these eldritch beings.

Other cultures documented dragons later, but China's archaeological record preserves the oldest physical manifestation, a tangible bridge between ancestral reverence and draconic mythology that won't be constrained by temporal boundaries.

Did Ancient Societies Believe Dragons and Serpents Were Real Creatures?

Dragon sightings and serpent legends weren't dismissed as fantasy but recorded as natural history across Mesopotamian tablets, Egyptian papyri, and Chinese chronicles.

Scholars documented chimeric creatures with the gravity reserved for lions or crocodiles. These weren't metaphors for the ancients; they represented tangible threats and divine manifestations, their existence unquestioned until Enlightenment rationalism severed humanity's connection to primal mysteries.

Conclusion

The mušḫuššu endures—not as mere artifact, but as threshold. These chimeric guardians, their scales gleaming across millennia, whisper truths humanity hasn't yet forgotten. From Babylon's dust-choked ziggurat steps to Berlin's sterile museum halls, the serpent-dragon coils through consciousness itself. What slumbers beneath such persistence? Perhaps these eldritch forms reveal something fundamental: that chaos and order, perpetually entwined, constitute reality's deepest architecture. The ancients knew. Their myths remember what we're still learning.